Who's Gonna Pay for the Pensions?

Suppose you're a free market capitalist. Companies that can't compete deserve to go under. Don't bail them out. Let the people who lose their jobs go to work for a company that knows how to make a profit.

Suppose you've entered the workforce in the 401(k) era. Defined benefit pensions are a relic, an artifact of the old unionist days, nothing to do with you.

Suppose you're a worker in one of those companies. You've already made salary concessions and seen the value of your company stock decline, but you're still qualified for a pension, and staying where you are seemed to be a better retirement plan than moving to another company and having to vest all over again. Especially given what you were hearing about Social Security.

Suppose you're a taxpayer and you hear that companies have underfunded their pension plans by $353.7 billion, a record shortfall, according to filings with the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC). That's an increase in underfunding — or a decrease in funding — of 27 percent in just a year. Since 2000, the number of underfunding corporations has grown from 221 to 1108, and the total then was only $19.1 billion. The PBGC is already the trustee for 3520 pension plans, including Bethlehem Steel, Polaroid, and TWA.

That means you'll eventually be on the hook, too, because the PBGC is facing a record deficit. The PBGC is not funded by general tax revenues, depending on "collecting insurance premiums from employers that sponsor insured pension plans, earns money from investments and receives funds from pension plans it takes over."

But the rates it charges were set in 1991, and Congress has shown no interest in raising them despite cautions from government analysts going back several years. Do some companies see a favorable tradeoff in paying the low premiums while continuing to contribute to their pension funds at less than realistic levels, given today's investment climate? Do they think if there's a problem they can walk away with a clear conscience, after handing the obligations over to the agency?

It's clear something is going on.

In the 2004 reports filed with the PBGC, the underfunded plans had $786.8 billion in assets to cover more than $1.14 trillion in liabilities, for an average funded ratio of 69 percent. Companies with less than $50 million in unfunded pension liabilities don't have to file reports, so the total shortfall in all insured pension plans, estimated by the PBGC, is more likely above $450 billion. You can see all this for yourself at the PBGC, which also presents an analysis of the pension plans of United Airlines:

"Although the plans have an aggregate funding shortfall of almost $10 billion and an average funded ratio of 41 percent, the company was able to go for years without making any cash contributions to the plans, without paying additional premiums to the PBGC, and without sending underfunding notices to plan participants."

Defaulting on pension obligations can look like a cynical ploy to collect corporate welfare in the form of a bail-out, but it's usually more complicated. As an article in Chief Executive explains:

"The problem of pension underfunding stems from a confluence of forces: the nation’s rising number of retirees, a drop in stock prices and historically low interest rates. Corporate America long relied on stock-market gains to offset soaring pension liabilities, but, given the current stock and bond markets, that is no longer an option. Interest rates are used in pension calculations as a proxy for the rate at which a pension fund must grow to pay future benefits. Low rates make pension obligations look much bigger today."

In other words, corporations don't ever set aside enough money to fully pay their pensioners. Like insurance companies, they rely on investing funds for growth, while counting on appreciation of their own stock value, plus some actuarial shrinkage (i.e., death) to reduce the amount they'll ultimately have to pay. And with market returns lower, more people ready to retire, and longer life expectancies, they're facing making up the difference at the very time their shareholders are likely to be getting testy about financial performance.

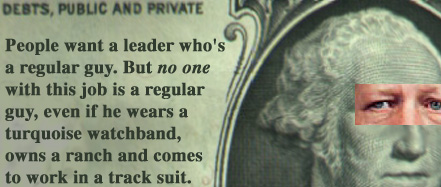

I think most corporations get in trouble because their executives are smart, but ego driven, not because they're crooked. They think they can work the angles of the law, beat the markets, fix earnings before the Street finds out there's a problem, etc. See Ken Lay, Bernie Ebbers and all the rest.

The Smartest Guys in the Room.

Though they may be disgraced, the execs responsible for their pension fund solvency don't face financial problems themselves. It's the working folks who end up collecting only a portion of what they were promised as part of their employment agreement.

As shareholders, we have to ask ourselves, do we care how these companies behave? Or are we simply worried about our own nest eggs?

Someone is going to have to pay for those past obligations. Will it be the corporate insurance premiums, the tax payers, the shareholders or the people who trusted the company they worked for?

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home