Them's Fightin' Words

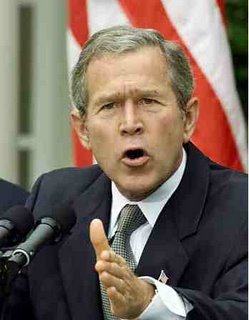

Colin Powell employs emphatic gestures to show the terrorists we would never "cut and run."

Colin Powell employs emphatic gestures to show the terrorists we would never "cut and run."As Congress has renewed debate over our Iraq strategy, we are seeing an orchestrated sprinkling of fighting words.

Pennsylvania Rep. John Murtha, a retired Marine colonel with a hawkish record on defense, called for withdrawal from Iraq, and the Administration first dispatched the chickenhawks. House Speaker J. Dennis Hastert of Illinois said "Representative Murtha and Democratic leaders have adopted a policy of cut and run" and accused Murtha of "insulting the troops." Majority Leader Roy Blunt said withdrawal talk will "embolden our enemies" and Rep. John Carter, R-Texas, said critics want to take "the cowardly way out."

Vice President Dick Cheney called questioning the Bush administration's use of intelligence before the war "one of the most dishonest and reprehensible charges ever aired in this city."

Murtha responded: "I like guys who've never been there that criticize us who've been there. I like that. I like guys who got five deferments and never been there and send people to war, and then don't like to hear suggestions about what needs to be done."

Owww.

Time to bring out the Republican Vets. Minnesota Rep. John Kline, a retired Marine colonel, called Murtha's comments "unconscionable. He should know better." Texas Rep. Sam Johnson, an Air Force vet and former Vietnam POW, laid down more fire using the same "unconscionable," according to an LA Times story.

"Reprehensible" should only be deployed by a skilled operative.

"Reprehensible" should only be deployed by a skilled operative.Unconscionable and reprehensible are the WMD of political bluster — big words that envelop their target in an accusatory ooze of reptilian immorality. People may not know what they mean, but they sure sound creepy. Words like these are to be deployed only by specially trained operatives because in the wrong hands, they are kinda hard t' pernounce.

Cut and run, on the other hand, is the all-purpose, plainspeaking way to imply frantic cowardice without actually saying it. You can practically hear the pantywaists scampering away when faced with a little adversity. Googling "cut and run" plus "Iraq" yielded 302,000 hits today. Expect the total to keep climbing.

"Cut & run" is easy t' pernounce.

In Sometimes a great notion, the Word Detective spells out the origin of cut and run:

A ship at anchor coming under sudden attack by the enemy, rather than waste valuable time in the laborious task of hoisting its anchor, would sacrifice the anchor by cutting the cable, allowing the ship to get under sail and escape the attack quickly. "To cut and run" was thus an accepted military tactic in emergencies, and the phrase itself dates to at least the early 1700s. By the mid-1800s, "cut and run" was in common use as a metaphor for abruptly giving up an endeavor in the face of difficulty, and appears in non-nautical context in Dickens's 1861 novel Great Expectations.

Sailors extended the metaphor to fit other hasty, though not panicky, departures: Herman Melville, in his 1850 novel, White-Jacket, had a midshipman cry out, "Jack Chase cut and run!" about a buddy who ran away with a seductive lady. The poet Tennyson wrote to his wife, Emily, in 1864: "I dined at Gladstone's yesterday -- Duke and Duchess there ... but I can't abide the dinners .... I shall soon have to cut and run."

That lighthearted sense has since disappeared. Like the word quagmire, the phrase has gained an accusatory edge in politics and war.

Gotta go....

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home